When political parties have their own intelligence agencies

REACTION: Trump campaign incident at Arlington National Cemetery

How deep could the divide between Democrats and Republicans get? I often ask myself that question, especially in the years that we choose presidents. The rhetoric at times makes it seem as though the two parties represent completely different countries, with their own historical grievances and priorities. And then I remember Kurdistan — and what it looks like when two major political parties are so divided that they possess their own intelligence and counterterrorism services.

It was the summer of 2016. My then-boyfriend and I had, from our couch, crowdsourced our way into a trip to the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq. Our plane diverted over Iran, since ISIS was burning oil to cloud the visibility above Syria. We touched down in Erbil, the capital, the day the coalition’s operation to liberate Mosul began.

We were the only Americans there to document the music and memories of people who had been displaced — by ISIS, by the war in Syria, and by the U.S. invasion of Iraq. And as we conducted interviews and gathered field recordings in refugee camps, we were followed by the Asayish, the domestic security agency of the Kurdistan Regional Government. That’s when I learned that the two main political parties had their own intelligence and counterterrorism units.

As both the U.S. and Kurdistan face acrimonious elections this fall, what follows is an exploration into the costs of divisiveness. And much of it is sensitive and has never been reported.

Rewind to the 1970s: Masoud Barzani, leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), breaks from the clan traditions of Kurdish tribesmen. His brainchild is building Parastin, an intelligence agency that has echoes of the Soviet model. (His father had made a famous walk, called the “Epic of Aras,” through Iraq, Iran, and Turkey to seek asylum in the Soviet Union three decades prior.) But a Kurd named Jalal Talabani splits from the KDP to found the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). Then comes Dazgay Zanyari, the PUK’s intelligence agency. “Separate and parallel agencies,” as Human Rights Watch once described them. And the divides are not just ideological, they are regional as well as familial.

The basics:

KDP = The Barzani family, who control the capital city of Erbil. They established the Parastin intelligence service and KCT counterterrorism service.

PUK = The Talabani family, who control the southern city of Sulaymaniyah. They established the Zanyari intelligence service and CTG counterterrorism service.

The 1980s for the Kurds were tumultuous — filled with Saddam Hussein’s repression, chemical weapons attacks, mass executions, and razed villages. By the early 1990s, the Kurds were trying to unify their security forces. But then a brutal civil war began.

“The whole civil war started over the ownership of a bakery,” a retired senior CIA case officer with decades of experience in Iraq told me. He was in Erbil when we spoke, and frequently travels to the region, so he requested anonymity out of concerns for his safety.

He was one of six CIA officers in Iraq back then. And he described how they drove back and forth between the two main cities of Erbil and Sulaymaniyah, “refereeing.” The CIA wanted to diminish the tensions between the parties and their intelligence services.

“We laid the law down and then told them, ‘Look, you can't act like this. The enemy is south of you in Baghdad. If you're going to exhaust yourselves, killing each other, we're going to leave and wish you well but we're out of here,’” he said. “And that got their attention. And then there was some hard fought meetings and arguing and yelling. They figured it out.”

Relations slowly improved. And in 1998, then-U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright brokered a peace agreement between the KDP and PUK. A generation fueled by hatred was slowly replaced by Kurds with a shorter list of sins, or more specifically, memories of them.

But since 2017, sources tell me relations between the parties and their security services have been at an all-time low. That was the year when the oil rich city of Kirkuk fell to Iraqi security forces. The KDP accused the PUK of selling out the Kurdish cause as PUK forces retreated.

“So Parastin and the Zanyari, they're back to their main roles, watching each other and fighting each other,” says Michael Knights, a renowned Iraq expert and the Bernstein fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Today it’s Moscow Rules in Kurdistan, he tells me. He described being in the capital, Erbil, and waiting for a ride to Sulaymaniyah. He spotted a car waiting at the right time and place, but with the wrong license plates. A Zanyari officer told him the driver had to change plates to avoid surveillance. “They track their people, they work out who they're meeting with. They find kompromat on them, they surveil them, they photograph them, they hack each other's emails. They're there to find out good stuff that's useful against the other party.”

One incident from the summer of 2021 still reverberates across Sulaymaniyah and Erbil. The Zanyari had an internal coup. Its leader, Lahur Talabani, was ousted by his cousin Bafel — the eldest son of PUK founder and former Iraqi president Jalal Talabani.

As Lahur had been rising in Kurdistan, Bafel was abroad, caring for his father who had a stroke in 2012. By 2017, Bafel was back in Kurdistan, bringing his father to their homeland in his last moments. He died just 12 days before Iraqi forces began to take Kirkuk.

Lahur and Bafel had an old friendship, and they began leading different parts of the PUK together, a true first for the party. Both had been among the first Kurds to work with U.S. special forces after September 11th, according to Mike. (“The Americans said, ‘You want to have your own special forces outfit that we'll support?’ And they're like, ‘Yeah, sure.’ And that became counterterrorism group CTG.”)

But Lahur also wanted to consolidate the PUK, “so that it was kicking back money to the party rather than people just siphoning it off individually,” Mike says. Meanwhile, his brothers were exploiting their position to overpower rivals. “Bafel could say, ‘Lahur's not running things properly, let's get rid of him,’” Mike said. “And they did. Overnight practically.”

Now he says Lahur is sitting in a fortified compound under glorified house arrest, with some approved travel. He has also registered a new political party called the People's Front Party.

The Zanyari’s split is personal to Mike, and it saddens him. “I knew them all,” he told me. “Most of them come from the exact same tiny corner in southeast London that I did. Most of the PUK intelligence guys are from what is the Croydon area of south London.”

Bafel grew up less than a mile away and is the same age as Mike. In the mountains above Sulaymaniyah, Mike has been inside the “Iron Lady bar,” a watering hole in Bafel’s villa — which he apparently took from the former president of Iraq, Barham Salih. There are commissioned portraits of Margaret Thatcher, Winston Churchill, and the Duke of Wellington. “And he was a big royalist too, he really loved the Queen.” Lahur was raised in Beckenham, a nicer part of London, and learned street Kurdish faster than his cousin, becoming “a good retail politician.”

At first, Lahur’s removal from power prompted MI6 to step in and help some of the Zanyari officers who would have been badly harmed. They were extracted to London. “The Brits made sure they didn't get killed,” Mike said. “They have very long term relationships with the Zanyari people.”

But not every Zanyari who supported Lahur Talabani went to England, and the clean-up continues. “[Some] have been picked off one by one, others co-opted, others went with the new regime and they were put in the ‘gulag’ for a couple of years and then they were considered to have detached from Lahur and have kissed the ring.”

Loyalists have been punished with demolished homes, a symbol to many Kurds of their power and prestige. Just in February, PUK security forces used demolition vehicles to level the house of a loyalist to Lahur in Sulaymaniyah. “It's three years later now, and there's still people being killed, driven out,” Mike says.

Where was the KDP’s Parastin in all of the chaos? After the coup, the agency took advantage of the Zanyari’s internal strife. It started taking in officers who fled to Erbil. Because they have deep knowledge of the PUK, Parastin have used them to create fifth column elements.

As a response, Bafel reached out to malcontents in Parastin, along with Iran and U.S. designated terrorists (Shia militias) in Baghdad to try to outpower the KDP.

With daggers drawn and tit for tats came a brazen assassination in Erbil in 2022. A Zanyari intelligence officer died when a bomb detonated in the SUV he was driving, wounding his two children and sister. The KDP blamed the PUK and lobbied the U.S. government to diminish its work with PUK’s counterterrorism unit (CTG), describing it as an act of domestic terrorism with American-trained officers. The CTG blamed the Parastin.

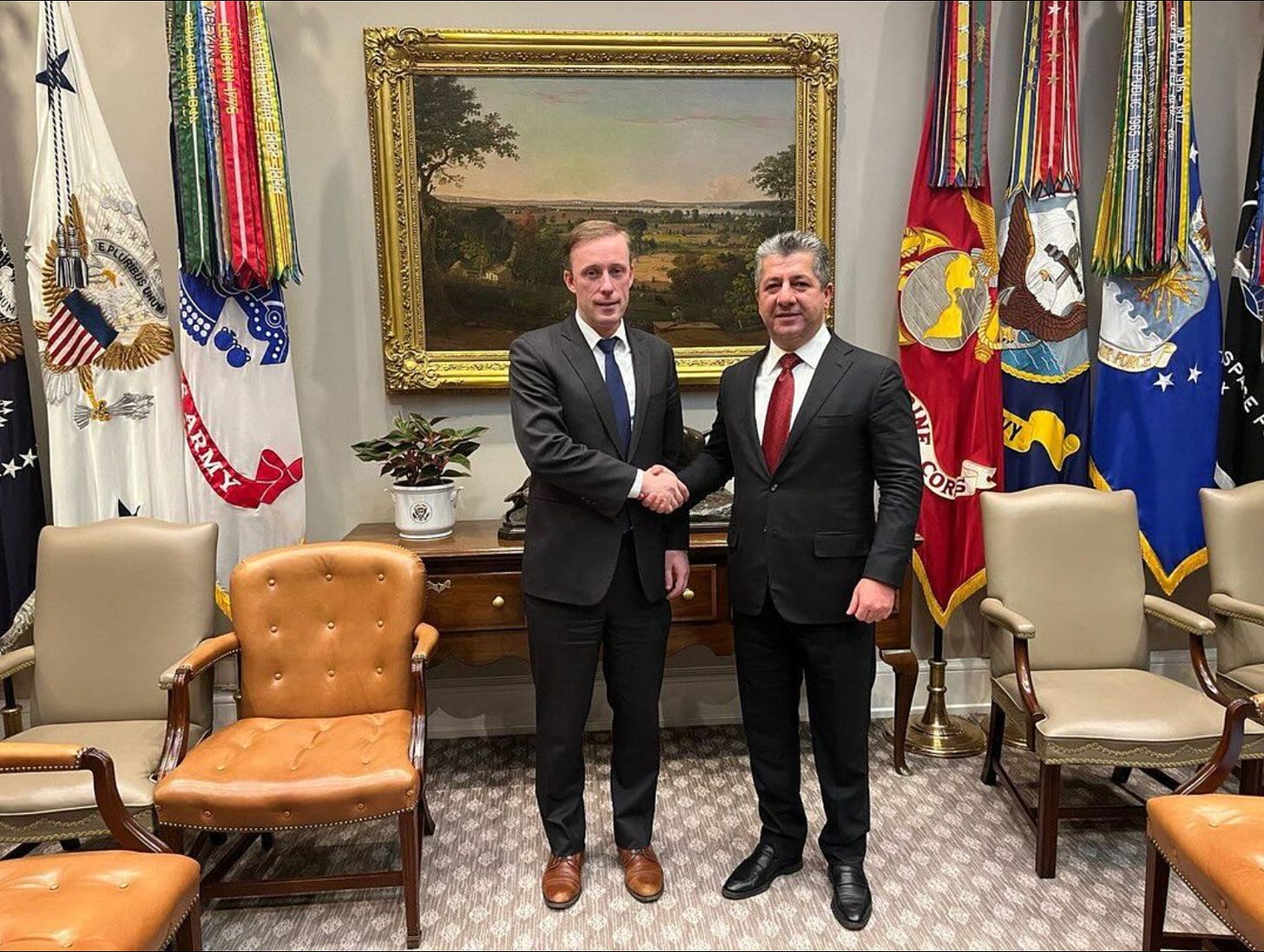

The murder severed communication between the political parties, a senior Kurdish official told me. And even though the KDP’s Masrour Barzani and PUK’s Qubad Talabani vowed to work together last year, with pressure from U.S. officials, the Kurdish official believes there is no counterterrorism or intelligence collaboration today. We spoke on the condition that I not publish his name, due to concerns for his life and livelihood.

In fact, simply reporting on the parties’ security services is dangerous, I learned. A public affairs officer at the Atlantic Council told me, “The subject might be very sensitive in Iraq especially with records of assassinations/kidnapping of researchers and think tank affiliated people digging into the militias/parties' structures.”

A fellow from the American Enterprise Institute wrote that under “the new Zanyari,” security forces have gone after domestic opposition, fired tear gas and live ammunition at protesters, and used “the U.S.-funded and equipped Counter Terror Group to go door to door arresting protesters.” Photographs allegedly show the body of a man who endured “electrocution, beating, and stab wounds after his arrest.” Parastin has also been accused of abuses.

When I ask Mike about both services’ track records, he tells me the parties built their intelligence wings in the image of the brutal agencies that hunted all Kurds —the Mukhabarat (Saddam Hussein’s main intelligence service), as well as their Iranian, Turkish, and Syrian counterparts. That they are remnants of the Cold War.

But the Kurdish official responded to the reports of abuse differently. “That's normal in this part of the world,” he told me. “Americans know that, and they continue to cooperate. So I think Americans are signaling — of course they won't say publicly — that they're okay with it too. Because at the end of the day, they want security objectives to be achieved and the rest can be tolerated.”

He accuses the U.S. of deepening the divide between the parties and their security services. “I have told American diplomats in D.C., in Erbil, you basically make these divisions deeper because you support their intelligence, their CT [counterterrorism] units, separately and directly... If you are looking for a long term strategic interest in Kurdistan, this is not in your interest.” I asked him what the Americans say to that, and he said, “It’s diplomats.”

And yet, despite his criticism of American diplomacy, he says only the United States has the power to sway both parties — and to ensure their existence. “All Kurdish leaders, with no exception, they know that the survival of this region depends on Americans. Not on any regional country. On Americans,” he said. “All Kurdish leaders know once America is out of this country, it will be over for Kurds.”

With the Kurdistan region’s parliamentary election set for Oct. 20, the official expects relations between the parties and their security services to get worse, with a war of words already breaking out on social media. He fears the formation of a coalition government could get ugly.

And because of the partisan divides, all of the Kurdistan region has become weaker in its dealings with Baghdad, which he described as “a forced marriage.” He went on to say, “We have zero leverage, we lost our pipeline, which was the backbone of our economy. And we are at Baghdad's mercy to send us budgets every month.”

Officials in the Kurdistan Regional Government are still waiting on their salaries for July, and last year they only received nine months of pay, he told me. Any fleeting deals with Baghdad are undermined by the opposing political party. “If you compare the situation before 2017 to now, basically we are toothless towards Baghdad.”

It seems that the rivalries that Baghdad was able to exploit when Saddam Hussein was alive are still ripe for the taking decades later, holding the Kurds back. Or do they hold themselves back by letting the divides grow and branch off? The United States does not have a Baghdad equivalent, but the chaos of our internal politics weakens its stance and policies with adversaries overseas.

REACTION: Trump campaign incident at Arlington National Cemetery

Trump's campaign stop at Arlington National Cemetery earlier this week was disastrous and despicable. I react to the latest headlines coming out from Trump's visit, and explain just how disrespectful he was while visiting our nation's most hallowed grounds:

With so much chaos going on everywhere it is more important than ever to make sure the right people are voted into power! Vote BLUE ALL down ballet too.

Thank you for cross-posting this fascinating article. As an interested but relatively uninformed observer of world affairs, I have long wondered why the Kurds did not have their own country. Superficially, it appears that the opposition of the governments of the four countries over which most of the Kurdish population lies (Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Syria) is sufficient to keep their aspirations in check. And the major foreign backers of those four countries' governments deem the desires of those governments to be more important to their own interests than the creation of a Kurdistan. However, it would also appear from this article that the enormous fractures within and among the Kurdish people also prevent the realization of this aspiration. Are the Kurds like the Palestinians in that regard? (Politically, I mean. I'm aware that the Kurds are a distinct ethnic and cultural group, and not just a subgroup of a larger ethno-cultural group).