The Truth About the Weaver Email

Galen Receives But Does Not Share the Weaver Email With Schmidt or the Other Management Committee Member; In-House Counsel Investigates the Email’s Vague Allegations and Determines No Action is Required and None is Taken

At no time was Weaver in physical proximity to anyone associated with The Lincoln Project after its launch in December 2019. He was based in Texas and never joined The Lincoln Project when it gathered in Park City, Utah. In August 2020, he would go on what he characterized as medical leave. Thereafter, Schmidt had very limited contact with Weaver and certainly had no direct knowledge of any details of Weaver’s personal life.

In the early days of The Lincoln Project, Weaver butted heads with Steslow. Galen had negotiated the contract between The Lincoln Project and Steslow’s company, Tusk Digital, whereby Tusk would serve as the organization’s data vendor. When Weaver saw the dollar amount of the contract, he demanded that it be renegotiated.

We now know that not long after this clash over the Tusk contract, in June 2020, Steslow—who then (unbeknownst to any of the founders other than Galen) was considered a member of The Lincoln Project board of directors—purportedly received the Weaver email from a senior Tusk employee, Conor Rogers. Steslow in turn delivered the Weaver email to Galen, also a board member, and to The Lincoln Project’s de facto general counsel.[14]

The email made non-specific accusations about Weaver having engaged in inappropriate, quid pro quo exchanges with adult men, mostly in their 20s. There were no names associated with the allegations. Most were secondhand (some were thirdhand) allegations based on stories Conor Rogers claimed to have heard. None involved minors. There was no backup or receipts, such as screen shots of messages, etc. The email only generally referenced dates that pre-dated The Lincoln Project’s launch, in some cases by years, including when Weaver worked for other campaigns, such as the 2016 John Kasich campaign.

Galen, however, did not elevate the Weaver email to Schmidt or Wilson, the other two members of the management committee. Neither did Steslow—who apparently was appointed to the board on the very same day he gave the Weaver email to Galen[15]—not then or ever. Schmidt was not otherwise made aware of the Weaver email’s possible existence until roughly eight months after it first surfaced in June 2020, when, on February 10, 2021, reporter Miranda Green of New York Magazine sent an email to Schmidt asking the following:

On June 17, 2020 Sarah Lenti and Reed Galen were sent a complaint from someone in the Lincoln Project flagging knowledge about Weaver's inappropriate social media interactions with people outside the company, as well as one employed by the Lincoln Project--were you ever aware of this complaint? What actions did the Lincoln Project take upon receiving this complaint? (Emphasis added.)

Schmidt immediately called and disclosed the existence of the Weaver email to Danny Hakim.[16]

As Schmidt now understands (he had no knowledge at the time), The Lincoln Project’s de facto in-house legal counsel investigated the allegations in the Weaver email. Given the lack of specificity in the allegations and the fact that the alleged conduct pre-dated The Lincoln Project, any investigation would have been difficult to be sure. The scope of counsel’s investigation, such as it was, remains unclear, although it is certain that Weaver was not interviewed. Whatever the investigation did entail, however, The Lincoln Project’s counsel concluded that no action was required and none was taken.

Weaver Goes on Medical Leave and Has No Further Involvement in The Lincoln Project

In or about July 2020, there were reports that The New York Post was working on a story that Weaver, who is married to a woman, is gay. For Schmidt, even if true, this information was hardly newsworthy, much less new—as far as Schmidt knew, this rumor had been circulating for more than a decade. Nevertheless, on August 3, 2020, Schmidt and Wilson called Weaver to alert him to the reports that the news story was forthcoming. In that conversation, Schmidt asked Weaver pointedly whether there was anything that The Lincoln Project founders needed to know. Weaver was unequivocal—he is not gay and there was nothing The Lincoln Project needed to know.

Then, the very next day, Weaver announced that he had suffered a heart attack and would be taking a medical leave from The Lincoln Project. Schmidt was taken aback but he knew that Weaver had cardiac health issues; in fact, that was the reason Weaver gave for having missed The Lincoln Project’s one and only public fundraising event in February 2020. Schmidt also had seen Weaver on a recent Zoom call in July 2020 and Weaver looked unwell.

After going on leave, Weaver had no further involvement in The Lincoln Project, although Wilson and Lenti would continue to stay in close contact with him through the November 2020 election and beyond. Lenti even would surreptitiously add Weaver to conference calls so that he could listen in.

Early January 2021: Following Media Reports About His Alleged Misconduct, Weaver Publicly Resigns from The Lincoln Project

In or around January of 2021, articles began to surface in various media, which reported allegations of misconduct against Weaver and questioned whether The Lincoln Project’s other founders had knowledge of the allegations and were complicit in covering them up. The first such article, “The Lincoln Project’s Predator,” by Ryan Gidursky, appeared in The American Conservative on January 11, 2021. Gidursky, an unabashed critic of The Lincoln Project, wrote of anonymous younger men who claimed to have been propositioned by Weaver and concluded the article by positing, “one of [The Lincoln Project’s] founding members was using the organization and the promise of a job in politics to prey on young men. The question remains, though, of how many other founding members knew about it and were complicit.”

Media coverage intensified over the next several days and continued to report about anonymous allegations against Weaver. On January 15, 2021, Weaver issued a public statement, in which he admitted for the first time that he is gay. He also addressed the allegations of his inappropriate communications with men: “To the men I made uncomfortable through my messages that I viewed as consensual mutual conversations at the time: I am truly sorry. They were inappropriate and it was because of my failings that this discomfort was brought on you.” Weaver also used his public statement to announce his resignation from The Lincoln Project: “I took a medical leave of absence from the Lincoln Project last summer and will not be returning to the organization, even after I fully recover.”

January 31, 2021: The Times Reports for the First Time About Specific Allegations of Misconduct About Weaver, Allegations Pre-dating The Lincoln Project In Some Cases by Years

On January 31, 2021, The New York Times published its article, “21 Men Accuse Lincoln Project Co-Founder of Online Harassment,” which also reported about allegations of misconduct against Weaver, although this time the allegations were not vague and non-specific or about unnamed accusers. Instead, The New York Times reported that Weaver “for years [at least as far back as 2015] sent unsolicited and sexually provocative messages online to young men, often while suggesting he could help them get work in politics.” These allegations were based on interviews with 21 men—only four of whom were identified by name—who claimed to have received such messages from Weaver. The article contained the account of one of the four men identified, who was 14 years old in 2015 when Weaver—then working for the John Kasich presidential campaign—first contacted him.[17] None of the men were identified as having any involvement with The Lincoln Project and, according to The New York Times article, all of Mr. Weaver’s contact with the men, save one text message exchange in March 2020, pre-dated The Lincoln Project’s launch.[18]

The Lincoln Project responded swiftly with a scathing indictment of Weaver. It posted a statement to Twitter the same day The New York Times article was published, January 31, 2021, stating in part, “Like so many, we have been betrayed and deceived by John Weaver. We are grateful beyond words that at no time was John Weaver in the physical presence of any member of The Lincoln Project.”

On February 11, 2021, The Lincoln Project announced that it would “retain a best-in-class outside professional to review Mr. Weaver’s tenure with the organization.” The Lincoln Project further announced that “any person who believes they are unable to talk about John Weaver publicly because they are bound by an NDA, should contact The Lincoln Project for a release.”

The Lincoln Project Engages an Outside Law Firm to Investigate Weaver’s Tenure with The Lincoln Project; Schmidt Voluntarily Participates in the Investigation

The Lincoln Project engaged the law firm of Paul Hastings to conduct the Weaver investigation.

Schmidt voluntarily sat with the investigators and gave them everything they requested and more.[19] Schmidt himself engaged a forensics expert to examine his cell phone across all messaging apps. He had nothing to hide. He even provided the investigators a declaration that he signed under criminal penalty of perjury, attesting to his lack of knowledge of any allegations made against Weaver, including the Weaver email. The sworn declaration also provided a detailed chronology of Schmidt’s time with The Lincoln Project, including the specific (and, in the case of the “co-founders,” limited) numbers of phone calls, emails, and in-person interactions with the other founders and “co-founders.” Among other things, Schmidt’s sworn declaration disproved what had been reported in the press, i.e., the allegations in the Weaver email “and others were discussed on subsequent phone calls with organization leaders in June and August.”

Schmidt catalogued his communications with the founders and “co-founders.” As he stated under oath in his declaration, he had a total of two conversations he had with anyone at The Lincoln Project about Weaver, one took place with Steslow in July of 2020 in which Schmidt encouraged him to sign his contract. During that conversation, Steslow expressed his dislike for Weaver. Steslow did not raise any concerns. The other was a five-minute phone call in August 2020 with Sarah Lenti. During that call, Lenti vented about what she described as Weaver’s verbal abuse toward her. There was no discussion about anything else related to Weaver. Thus, it was shocking for Schmidt to learn that Lenti had gone on record with reporters, including Amanda Becker with the19thnews.org, falsely asserting that he had known about allegations of sexual misconduct involving Weaver as early as March 2020.

The Times Falsely Reports That The Lincoln Project Leadership (Beyond Galen) Knew of Specific Allegations of Misconduct Involving Weaver; Its Anonymous Sources are Deeply Compromised and Motivated to Provide Less than Accurate or Truthful Information About The Lincoln Project

On March 8, 2021, The New York Times published “Inside the Lincoln Project’s Secrets, Side Deals and Scandals.” The article was largely based on anonymous sources, purportedly “people with direct knowledge.” Under the heading, “Unaddressed Complaints,” The New York Times reported on the Weaver email and purported to quote from it. But, as the article revealed, The New York Times had “obtained [only] a portion” of the Weaver email; however, the article is silent as to how it obtained it. The article merely states that “multiple people who have read [the Weaver email] provided detailed descriptions of the rest.” None of these multiple people were identified. Yet, it is evident who they were—the limited number of people who had access to the Weaver email at the time (other than the outside investigators) were Steslow, Steslow’s second-in-command, Conor Rogers, Mike Madrid, the other board member, Galen, and the Lincoln Project’s in-house counsel. The New York Times reporters spoke with Steslow, Madrid, and Lenti, all of whom were quoted in the article. Galen did not speak to the reporters; neither did in-house counsel.[20]

So, it would seem that the only possible sources of information about the Weaver email, including the “portion” of the Weaver email The New York Times received, were Steslow, Rogers, and/or Madrid. But having quoted each of them elsewhere in the article, including them as some or all of the “multiple who have read” the Weaver email is an unambiguous violation of The New York Times policy of the (disfavored) use of anonymous sources—“The Times does not dissemble about its sources — does not, for example, refer to a single person as “sources’ and does not say “other officials’ when quoting someone who has already been cited by name.” (Emphasis added.)

Moreover, based on the information contained in the article itself, Steslow, Rogers, Madrid, and Lenti each had a motivation to selectively leak a “portion” of the Weaver email, devoid of context and provenance, and to otherwise provide information about The Lincoln Project that was less than complete or accurate. In fact, The New York Times article touches upon some of the possible motivations but gets them wrong. And, because none of Steslow, Rogers, and Madrid are identified as sources of the information about the Weaver email, the reader would not be able to draw those connections, even if correct. For example, the article reported that:

Axios reported in late October [2020], that the Lincoln Project was ‘weighing offers from different television studios, podcast networks and book publishers.’ That was news to Mr. Steslow, Mr. Madrid and Ms. Horn, according to three people with knowledge of the matter. It exacerbated tensions that had been simmering since the summer, when the trio had resisted a brief effort by the original founders to strip them of their titles as co-founders, the people said.

By Oct. 30, Mr. Steslow, Mr. Madrid and Ms. Horn were already on edge as they gathered at Mr. Schmidt’s Utah house, listening as he outlined his vision for a media company. And it was soon made clear to them that they would not be equal partners…

The article goes on to report about the “bitter standoff” that began “[n]ot long after the election” between Steslow and Madrid, on the one hand, and Galen, Wilson, and Schmidt, on the other, about Schmidt and Wilson being given board seats, and that ultimately “a settlement was reached with Mr. Steslow and Mr. Madrid, who departed in December [2020],” while Schmidt and Wilson were appointed to the board. Without question then, the reader should have been told about the anonymous sources’ (Steslow and Madrid’s) “known motivations” arising from, among other acrimony, their reported “bitter standoff” with Galen, Wilson, and Schmidt only a few months earlier.

And, although the story mentions, almost as an afterthought, that “[i]n January [2020], five months before the [Weaver] email was sent, another person working for Tusk had raised concerns with Mr. Steslow,” there is no further discussion or about Steslow’s earlier knowledge—at a time when not even Galen or the other management committee members are alleged to have known. Nor is there any scrutiny as to why Steslow had not surfaced the concerns in January 2020, when there was no discord, or why, in March 2021, following a purported “bitter standoff” with Galen, Wilson, and Schmidt, Steslow would provide a “portion” of the Weaver email to reporters.

In fact, there was not a “bitter standoff,” but rather, as Schmidt considered it, coercive negotiations—first by Steslow and Madrid and then by Horn.

Neither Schmidt nor Wilson knew that there supposedly was a functioning board of directors and was incredulous that one could have been formed outside of the management committee—The Lincoln Project had operated as a roughly $90 million super PAC for all of 2020 without the so-called board of directors convening, much less making any strategic or other decisions, which it would not have had the authority to do in any event. In effect, the management committee was the board and, if by some requirement of Delaware corporate law they should have more formally designated themselves a board of directors and each of them directors, then Galen should have worked with The Lincoln Project’s corporate counsel to effectuate this.

In November 2020, as the euphoria of the Trump defeat and Biden triumph abated, Madrid—now not only a contractor and vendor but also a purported board member with fiduciary duties to The Lincoln Project—demanded additional compensation beyond what he had been receiving under his contract with The Lincoln Project. Madrid complained to Galen that he, Madrid, had made great (but unspecified) sacrifices for The Lincoln Project (more so than anyone else involved in The Lincoln Project), which had gone unacknowledged and unappreciated. In fact, by all objective measures, The Lincoln Project was Madrid’s most remarkable success of his political career. He dubiously claimed that he had earned $800,000 the year before joining The Lincoln Project; yet he signed a contract for a full-time position with The Lincoln Project that would pay him less than 10% of that amount. Galen capitulated to Madrid’s demands and paid him additional money.

At or around the same time and also unbeknownst to Schmidt, The Lincoln Project’s in-house legal counsel allowed the purported three-person board—of Madrid, Steslow, and Galen—to vote on a resolution to pay Madrid and Steslow $150,000 each for the purpose of initiating litigation against The Lincoln Project, which, not long after, both threatened to do. If the conflicts of interest inherent in appointing Madrid and Steslow to the board had not been evident previously, they certainly should have come into sharp focus for him at this time.

It was then that Schmidt and Wilson learned for the first time that a board purportedly had been constituted whose membership was bound up in shocking conflicts of interest. Schmidt also realized that Galen had lost control of the organization and that the organization was unraveling as people got swept up in The Lincoln Project’s meteoric success and the fame (or notoriety) that went along with it and, worse, completely lost sight of The Lincoln Project’s original mission. For Madrid, Steslow, and Horn, their already outsized sense of entitlement as nominal “co-founders” became even greater, each believing (wrongly) that he or she should be equal partners in any Lincoln Project-related venture.

Schmidt stepped in and demanded that he and Wilson, as two of the original founders, be appointed to the board immediately. To that end, on or about November 23, 2020, a resolution was proposed that would expand the number of board seats to five and would appoint Schmidt and Wilson to the board. Madrid and Steslow, however, refused. Instead—notwithstanding their fiduciary duties as purported board members, they made what Schmidt considered to be corrupt demands.

Steslow, whose company, Tusk, was the sole holder of The Lincoln Project’s data, would not release that data, including donor mailing lists and social media data and passwords, unless and until the negotiations were concluded. This was the clearest sign that Galen had lost control—The Lincoln Project’s data was being used as currency in a fight over who would control the organization.

Schmidt demanded that The Lincoln Project’s legal counsel declare that the so-called board was illegitimate and without authority to act on behalf of The Lincoln Project. Schmidt also insisted that there be a referral to the FBI for data theft. The Lincoln Project’s counsel refused.

Stuart Stevens had introduced another attorney to the members of the management committee, attorney Scott Labby—a self-styled “Michael Clayton,” whose “background [is] working for high net worth families as a problem solver.” Stevens endorsed Labby as being the best suited to advise the members of the management committee regarding the Steslow-Madrid crisis.

Schmidt was not impressed. He advocated for another lawyer who was far more credentialed than Labby and whose experience eclipsed Labby’s. Labby, obviously threatened by the other lawyer, made a series of unfounded accusations against him in an apparent effort to torpedo that lawyer’s attorney-client relationship with The Lincoln Project.

The Temporary Transfer of $1.5 Million of Lincoln Project Funds to Schmidt’s SES Strategies, LLC

With Labby on board and fearing that Steslow and Madrid—who were now known to have signatory authority over The Lincoln Project’s bank accounts—would plunder and otherwise destroy the organization, the members of the management committee concluded that immediate protective measures were necessary and in the best interest of The Lincoln Project. They agreed to temporarily transfer $1.5 million of The Lincoln Project funds to SES Strategies, LLC, Schmidt’s firm. The funds, which had been committed to the Stacey Abrams organization in connection with the important upcoming Georgia Senate races, would be held in trust by SES Strategies to prevent them from being misappropriated or misused. Once the situation was resolved, the funds were immediately returned to The Lincoln Project.

Although Labby was not Schmidt’s first choice, Labby was now representing the members of the management committee on the advisability of a possible settlement with Steslow and Madrid. Labby was dismissive of Schmidt’s stated concerns, including about the amount of money Steslow and Madrid were demanding and the manifest conflicts of interest the two had. Labby urged the members of the management committee to settle notwithstanding these and other concerns, making the point that the settlement would be made with “other people’s money.”

As for Horn, she leveraged the fallout caused by Galen’s mishandling of the Weaver email to try to enhance her contract negotiations. Capitalizing on the conflagration of devastating press, Horn made a series of what Schmidt and others considered unjustified financial and other demands on the organization. At about the same time, The Lincoln Project’s founders learned that Horn had been communicating with reporter Amanda Becker, promising to share with her supposedly damaging information about The Lincoln Project. Schmidt and the other founders learned of these direct messages through a Lincoln Project senior staffer Horn secretly had hired to also serve as her personal publicist and who therefore had access to Horn’s messages, though, Ms. Becker reported in her story that Horn “had neither provided the images to the Lincoln Project nor had she given another individual permission to access her account.” And, in the end, the staffer was forced to make the difficult choice—maintain Horn’s confidences at the risk of destroying The Lincoln Project or betray those confidences so as to serve and protect the organization. The staffer chose the latter. For The Lincoln Project, the choice was not so difficult—The Lincoln Project’s founders chose to release the direct messages.

When The Lincoln Project was criticized for its decision, Schmidt publicly acknowledged the mistake, took responsibility for it, and apologized to Horn (and the reporter). At the same time, recognizing that an act of leadership was required in light of this issue and the Weaver issue, Schmidt resigned from The Lincoln Project board of directors, making way for the appointment of a female director to a board constituted of all white middle-aged men.[21]

Horn, like Steslow and Madrid before her, had been given extraordinary, potentially career-defining opportunities through The Lincoln Project. In Schmidt’s estimation, each of them squandered those opportunities by their fame-seeking and quest for political and/or personal power, a phenomenon that sadly pervades culturally.

The Aftermath of the False Reporting About the Weaver Email

The Paul Hastings investigation Galen had commissioned in February 2021, concluded four months later, in June 2021. Schmidt urged complete transparency, which, in his judgment, would have included publicly releasing the report of the investigation. When that recommendation was rejected, Stuart Stevens took lead in drafting a statement that provided specific information about the scope of the investigation and its findings. That, too, was rejected. Instead, the outcome of the investigation was announced in a June 18, 2021, memo addressed to “Supporters of The Lincoln Project” posted on Twitter. This memo, from two staffers who were

identified as members of a so-called “Transition Advisory Team,” explained:

The investigation was initiated after news reports in January 2021 alleged that Mr. Weaver had, previous to his tenure at The Lincoln Project, engaged in inappropriate conversations with underage individuals. This investigation found no evidence that anyone at The Lincoln Project was aware of any inappropriate communications with any underage individuals at any time prior to the publication of those news reports.

Additionally, the investigation found no communications nor conduct reported to The Lincoln Project or its leadership involving Mr. Weaver and any employee, contractor, or volunteer that would rise to the level of actionable sexual harassment.

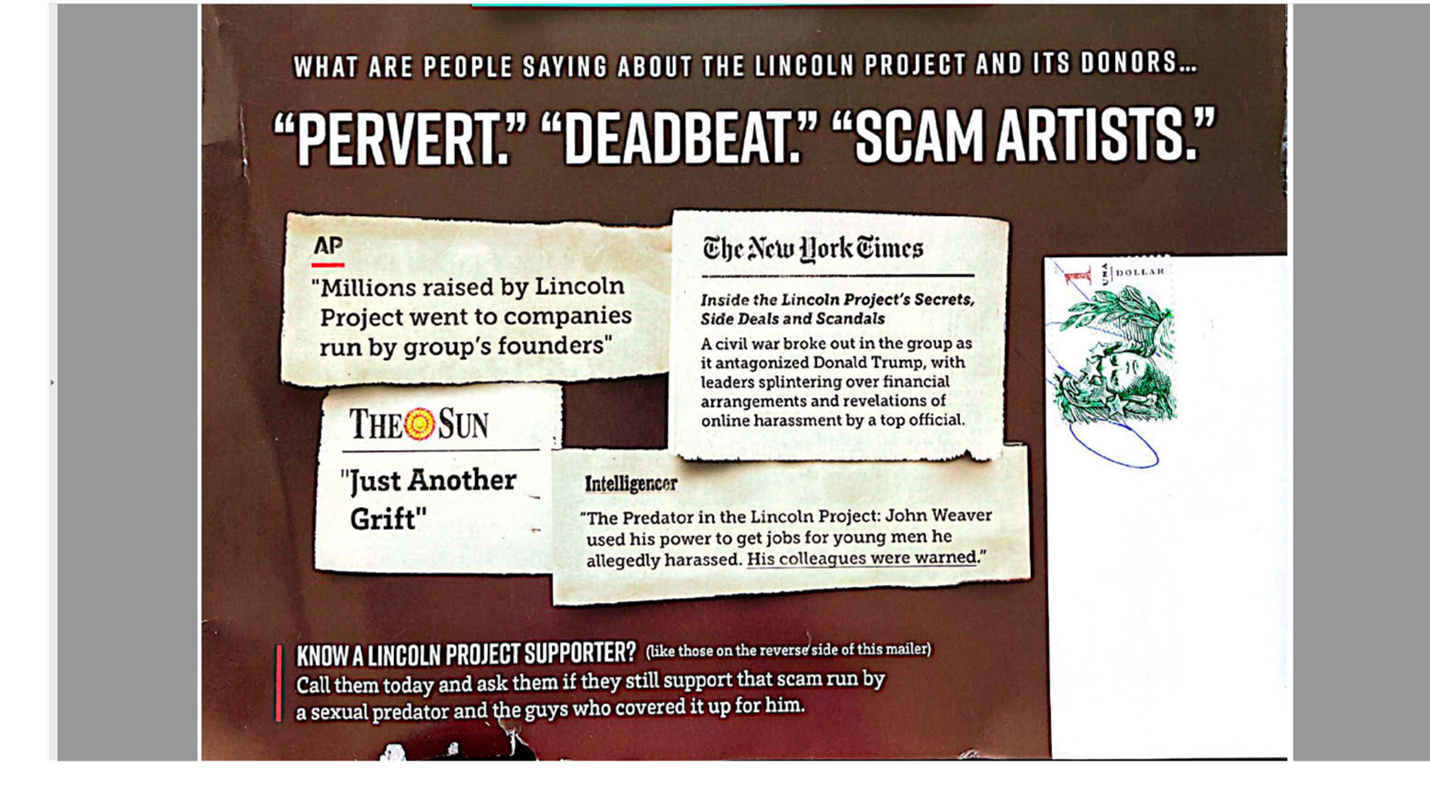

Although the investigation exonerated The Lincoln Project and its founders, what had been falsely reported by The New York Times and other publications about The Lincoln Project’s alleged knowledge of the allegations against Weaver caused ineffable and lasting damage to Schmidt and others. For The Lincoln Project’s detractors, the false reports represented ready-made incendiary devices, which were quickly deployed. In early March 2021, hateful, slanderous flyers were sent anonymously to The Lincoln Project’s founders and to thousands of its major donors and their neighbors and associates. These color-printed mailers read, “WARNING: PREDATORS ALL OF THEM ARE GUILTY” and falsely and recklessly accused the founders and major donors of, among other loathsome conduct, “HARBORING A SICKO WHILE HE PREYED ON YOUNG BOYS” and “bankrolling a grift that enabled a sexual predator.” Excerpts of various articles were cut-and-pasted on the flyers, including of The New York Times’ Inside the Lincoln Project’s Secrets, Side Deals and Scandals:

The New York Times did not report about the flyers.

For Schmidt, The Lincoln Project was never intended to be a career or a money-making venture. Schmidt had a noteworthy career before The Lincoln Project, both in and outside of politics. To assume his role with The Lincoln Project, Schmidt had to give up his MSNBC contract where he served as a political commentator, and he had to resign from a corporate board. And, because of the nature of The Lincoln Project’s work, Schmidt had legitimate concerns about the loss of clients and in turn income in the consulting space. So, the suggestion that The Lincoln Project was a vehicle for Schmidt to cash in or for his self-aggrandizement is simply not true. For others, perhaps, that is what The Lincoln Project was to them.

In the aftermath of all of these events, in the Fall of 2021 (as he was recovering from a broken back and while the world as we knew it was collapsing), Schmidt ended his association with The Lincoln Project. He had seen this movie before and knew how it would end. Once was enough.

* * *

Based on the foregoing, on behalf of Mr. Schmidt, we demand that The New York Times (1) issue a complete, immediate, and full-throated correction of its false and misleading reporting about The Lincoln Project and Mr. Schmidt, and (2) undertake a very serious review of its reporting on these subjects with a new, unbiased, uncompromised reporting team. What took place is disquieting, to be kind. If it could happen to Mr. Schmidt, it could happen to any American.

All rights reserved.

Cordially,

KERRY GARVIS WRIGHT

************************************************************************************************************

Footnotes:

[1] “This is harassment and it is unacceptable.”

[2] Ms. Haberman and Mr. Baquet acted contrary to the New York Times Social Media Guidelines for the Newsroom (“NY Times Social Media Guidelines”), which caution, “If the criticism is especially aggressive or inconsiderate, it’s probably best to refrain from responding. We also support the right of our journalists to mute or block people on social media who are threatening or abusive. (But please avoid muting or blocking people for mere criticism of you or your reporting.)” Ms. Haberman herself is quoted in the NY Times Social Media Guidelines, “Before you post, ask yourself: Is this something that needs to be said, is it something that needs to be said by you, and is it something that needs to be said by you right now? If you answer no to any of the three, it’s best not to rush ahead.” Regrettably, she did not follow that advice when she posted to twitter a “flashback” to her earlier, 2016 false report that Mr. Schmidt had met and spoke with Trump about a position within his presidential campaign.

.[3] “The use of unidentified sources is reserved for situations in which the newspaper could not otherwise print information it considers newsworthy and reliable. When possible, reporter and editor should discuss any promise of anonymity before it is made, or before the reporting begins on a story that may result in such a commitment. (Some beats, like criminal justice or national security, may carry standing authorization for the reporter to grant anonymity.) The stylebook discusses the forms of attribution for such cases: the general rule is to tell readers as much as we can about the placement and known motivation of the source. While we avoid automatic phrases about a source’s having “insisted on anonymity,” we should try to state tersely what kind of understanding was actually reached by reporter and source, especially when we can shed light on the source’s reasons. The Times does not dissemble about its sources — does not, for example, refer to a single person as “sources’ and does not say “other officials’ when quoting someone who has already been cited by name. There can be no prescribed formula for such attribution, but it should be literally truthful, and not coy.” The New York Times Guidelines on Integrity (Emphasis added.)

[4] Ms. Hsu is a “media reporter for the business desk, focusing on advertising and marketing” and her story appeared online in the Daily Business Briefing, as opposed to Politics where all other Lincoln Project stories appeared online. The print versions of The New York Times’ stories about The Lincoln Project all appeared in Section A, either page 1 or 17.

[5]Toyota says it will stop donating to Republicans who contested the election results.

[6] In the Fall of 2020, The New Yorker reported that “The Lincoln Project [had] 2.3 million Twitter followers—a number approaching that of the Republican Party’s official account…” That number grew to more than 2.7 million followers by November 2020.

[7]Not long after The Lincoln Project was announced in the December 17, 2019 New York Times op ed, the COVID-19 outbreak spread to the US. The Lincoln Project held one public fundraising event before the subsequent lock down, an event at the Cooper Union in New York on February 27, 2020, the 160th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s historic speech there.

[8] George Conway also was a nominal “co-founder” with no financial ties to the organization.

[9] There were only four true founders—Schmidt, Wilson, Galen, and John Weaver. As Weaver exited, Stuart Stevens assumed Weaver’s role within The Lincoln Project, including as a member of the management committee.

[11] Mr. Schmidt recalls that Ms. Haberman originally told him and Rick Wilson that she knew about these allegations ten years ago. She has since walked that back, claiming it was not ten years ago, but three—which is still years longer than when Schmidt first became aware. See March 23, 2022 Twitter post.

[12] The Lincoln Project had only existed for a year as of the date of the article’s publication; it was registered with the Federal Election Committee on December 9, 2019 and announced on December 17, 2019. (It had been registered under a different name on November 5, 2019.)

[13] It is unclear from the article when in 2016 Weaver was sending messages to Mr. Allen. Kasich suspended his 2016 presidential campaign in May 2016, making way for Donald Trump to be the presumptive Republican nominee.

[14] Reporter Miranda Green later would assert in an email to Schmidt that Steslow also provided the Weaver email to Lincoln Project contractor Sarah Lenti, who was neither a board member nor a member of the management committee.

[15] Corporate filings show that on June 17, 2020, Steslow, Madrid, and Galen were appointed to the three-person board of directors.

[16] Conor Rogers’ focus in the email was on the impact the allegations might have on The Lincoln Project’s reputation and public image, and not on the victims and the impact Weaver’s conduct might have had on them. As The New York Times reported, the email began “In addition to being morally and potentially legally wrong, I believe what I’m going to outline poses an immediate threat to the reputation of the organization, and is potentially fatal to our public image.’

[17] The New York Times reported that “At the time [2015], [the 14-year-old] supported the Republican Party and was a fan of Mr. Kasich, the Ohio governor whom Mr. Weaver was helping to prepare the presidential race.”

[18] One of the four men named “said Mr. Weaver had begun messaging him in July 2019. That exchange tapered off, but on December 3, 2019 – two weeks before the Lincoln Project was publicly announced – Mr. Weaver invited him to join the initiative.” (Emphasis added.) However, as The New York Times reported, the man never called Weaver and never joined The Lincoln Project.

[19] Participation in the investigation was voluntary and not everyone participated, including certain “co-founders.” Other “co-founders” did not sit for interviews; instead, the investigators were directed to communicate with their respective lawyers.

[20] “Mr. Galen was made aware of the June email, the five people with knowledge of the matter said; he declined to comment on the issue, citing the outside legal review the Lincoln Project has commissioned.” “Mr. Sanderson declined to comment, citing the legal inquiry.”

[21] See Feb. 12, 2021 statement.

This clarifies much for me. I think you did take blame when it was due. Like with Horn and the reporter. I feel like the people with integrity are never the winners. No one trusts Haberman so no need to put too much effort into explanation. We see her bias every day. Little by little you are gaining your reputation back and holding people accountable including yourself. Refreshing to say the least! Thank you.

As someone once said “No good deed goes unpunished”. TLP was such a great idea and did so well with the 2020 elections. I just hate what happened.

Since it is SES Truth Week will there be more truths coming?

Seriously, thank you. I truly love watching you tell it like it is and hope you will keep on doing it.