The law was perfectly clear. The three tea-laden whalers, merchant vessels flying the flag of his Britannic Majesty King George III, had 20 days to unload their cargo and pay the duties lest the ships and cargo be seized by royal authorities. A great drama was playing out up and down colonial America’s port towns of Charleston, New York and Philadelphia. Tax collectors were refusing to collect duties and enforce the monopoly of the East India Company to dump low-cost tea into the American market with preferential treatments at the expense of American merchants, sailors and laborers. The duties known as the Tea Act were imposed by fiat, without representation and they were despised and opposed. Without anyone to unload the cargo of British merchant vessels laden with East India Company Tea, or any merchants that would sell it, the solution to the quagmire was a simple accommodation. The ships that could not be unloaded were turned around and left before their property could be confiscated under the law.

This held everywhere except the Massachusetts Bay Colony where the Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson was determined to enforce the law. Once a ship had entered the harbor it could not leave without the governor’s permission, and Hutchinson would not give it. He insisted that the tea be off-loaded, and duties collected. The harbor was entered and exited through a narrow channel that was ringed with British 32-pound cannons and guarded by two heavily armed warships of His Majesty’s Royal Navy. The royal governor controlled the cannons and the warships. His cards were on the table.

The crowd that gathered during the 20-day tea crisis grew throughout. Nearly every single man from Boston and many from neighboring towns like Lexington and Concord were gathered together at the Old South Meeting House listening to orations by patriot leaders like the Reverend Warrenton, Josiah Quincy and Sam Adams. It is estimated that there were more than 7,000 men at the Meeting House when final word came that Governor Hutchinson would not bend. It was a cold December night with a small sliver of moonlight when the men set out for the wharf. Perhaps as many as 1,000 witnessed the events, and they included a British admiral who watched from his home and later saw the perpetrators march by accompanied by fife and drums in a celebratory march. History records his rejoinder to the celebration as an ominous threat.

Admiral Montague watched the whole affair from a house on Griffin’s Wharf, but gave no orders to stop the “Party.” When all was through, the “Mohawks” marched from the wharf, hatchets and axes resting on their shoulders. A fife played as they paraded past the house where British Admiral Montague had been spying on their work. Montague yelled as they passed, “Well boys, you have had a fine, pleasant evening for your Indian caper, haven’t you? But mind, you have got to pay the fiddler yet!”

The crowd headed towards the Boston wharfs, with the Sons of Liberty marching in the front, many dressed like Mohawk Indians. Their faces were painted, concealed and covered. They came at low tide, and boarded His Majesty’s Ships The Dartmouth, Beaver and Eleanor, and proceeded to dump 92,000 pounds of East India Company Tea into Boston Harbor so that the “fish could have a cup of tea,” according to one participant. The value of the tea adjusted to today’s prices was roughly $1,700,000.

What happened next was a series of escalatory events that would change world history, shatter the divine right of kings, and demonstrate an unflagging aspect of the American character: defiance. When the deadly struggle known as “The Cause” came to an end at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, the world had been turned upside down. A 23-year-old French nobleman named Gilbert du Montier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette, was there in command as a major general of the Continental Army. When the white flag appeared over British lines it is said he explained: “Humanity has won its battle. Liberty now has a country.”

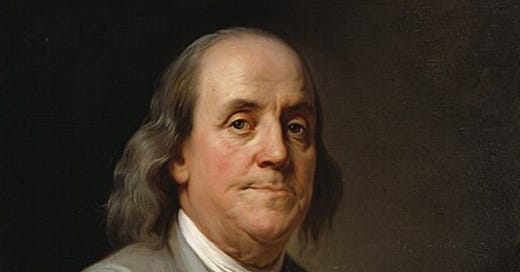

Benjamin Franklin was born in the early years of 18th century, the 15th child of Josiah Franklin and Abiah Folger. The couple were part of the 260,000 settlers, adventurers, religious pilgrims and children of the first settlers that laid claim for the English crown on North American soil. They shared the continent with hundreds of Indigenous tribes that had lived in harmony with nature for 600 generations and numbered in the millions. North of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was New France and approximately 10,000 Acadians.

The world was changing, expanding, evolving and the future was being invented one idea at a time. Notions of liberty, human rights and political freedom were bubbling like boiled water.

Franklin was a man of his age; he was a genius, inventor, philosopher and deeply subversive. He lived in an era in which a civilization was rising into existence and where there was freedom, opportunity and prosperity for ordinary people the likes of which had never been known throughout human history.

Franklin invented bifocals, and the lightning rod as part of ground-breaking experiments with electricity, paper money, the existence of the Gulf Stream, the first public libraries, insurance companies, volunteer fire departments and dozens of other public institutions that remain recognizable anchors of modern civil society.

He was a printer by trade who became a tremendously influential and important communicator in early America. He published newspapers, ideas and articles that connected a growing country of isolated communities into a network of thriving communities. He became the first postmaster general of the United States, and helped build the infrastructure of human connection that forged a nation in time. When he was a young man and apprenticed to his brother James in the printing shop, he was denied the opportunity to print a letter of his own in the paper. He rebelled by assuming the alias of a woman named Silence Dogood and succeeded in getting his work published in the “New England Courant.”

When James was imprisoned for printing criticisms of the Royal governor, Benjamin assumed a secret identity and penned letters under Mrs. Dogood’s signature that included this imagined quote from Caesar’s ceaseless foe Cato: “Without freedom of thought, there can be no such thing as wisdom, and no such thing as public liberty, without freedom of speech.”

Among the most famous, wealthiest and self-made men of the American colonies, Franklin spent between 1757 and 1775 living in London as a colonial agent representing and advocating for various American interests in the ever-growing colonies of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia and Massachusetts. All of the colonies were rumbling and straining against edicts, declarations and ad hominem decisions from London that affronted their sense of fairness and liberty. Benjamin Franklin was the proverbial man in the middle. There was no place hotter to be in colonial America than being involved in representing the interests of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in early 1770s London.

Dr. Franklin was the most famous and admired American of his era, both within the colonies and England. He was not a radical demanding independence, but a pragmatist looking to reach accommodation. He believed that reasonable minds could prevail in a dispute between Englishmen about their rights.

Thomas Hutchinson, the colonial governor of Massachusetts and a friend and long-time ally of Benjamin Franklin, had come to a point of view about what should be done about the ornery, unreasonable and increasingly belligerent colonial population of the Bay Colony. He argued for repression and harsh measures, including restrictions of liberty. Franklin was shown confidential correspondence about this in 1772 and faced a decision. He was, after all, the deputy postmaster general of North America and a loyal subject of the King, who did not wish to see revolution or escalations that would harm his fellow Americans and hurt their prosperity. He decided to betray his old friend and hang him out to dry.

Benjamin Franklin covertly sent secret copies of Hutchinson’s letter and recommendations to the King’s ministers for an “abridgment of liberties” to the leaders of the Massachusetts Assembly. His hope was that the most radical voices would turn like bulls towards a red cape and charge at Hutchinson and away from the British Parliament. The strategy was to create conditions where cooler heads from the middle could prevail. The idea was that Parliament would reject Hutchinson’s intemperance as madness, and the Sons of Liberty could be accommodated by his removal and a seeming concession from London. It was not to be.

Instead, the secret letters caused outrage and were printed in colonial papers from Massachusetts to Georgia. The rare printing presses and first newspapers of the first quarter of the century had become ubiquitous at the edge of its last quarter. The colonial population stood at 2,400,000, and included 500,000 Black people, approximately 450,000 who were enslaved.

The Massachusetts Assembly took action, denounced Hutchinson and passed a resolution demanding King George III remove his governor. The petition would be delivered to the King’s privy council and presented by Benjamin Franklin, the agent of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who felt honor-bound to disclose that it was he who had secretly sent copies of the offending letters to the Massachusetts Assembly in the first place.

His admission was utterly and appallingly scandalous. He was scheduled to appear in a room known as the “Cockpit” at Whitehall in late January of 1774. Things went from bad to worse for a man who had passed through a portal from reverence and respect to disdain and anger in the eyes of the people before whom he would soon be standing chastened. America’s most famous man was about to be humiliated when word arrived via ship about what had transpired in Boston on the night of December 19th.

London was aghast, The Privy Council enraged, and the King’s ministers were determined to avenge the disrespect towards the Crown, the law and their authority. Benjamin Franklin would be the first victim, and on January 29, 1775, he stood alone in front of the privy council in the room where Henry VIII would entertain his court with cockfighting. Now, it would be Franklin’s turn to be torn to pieces.

Lord Earl Gower did the work. He assaulted America, the colonists, the colonists’ character, Franklin’s character and their collective unworthiness. It was a brutal takedown. Throughout it, Franklin stood silent, stoic, unresponsive and perfectly still. He did not defend himself. He did not choose to answer any interrogatories. Shortly thereafter, he was dismissed in disgrace from his role as deputy postmaster general of North America and set home towards America for the first time in 16 years, minus the 18 short months he had spent in Philadelphia.

The most famous man in America was 70 years old, and his greatest achievements lay ahead as would become more clear when he arrived in Philadelphia to a rapturous reception in the late spring of 1775.

The actions of His Majesty’s government towards the rebellious colonies took the form of collective punishment for Boston and Massachusetts, which was aimed at warning the other colonies about the consequences and price of disobedience towards British authority. There was no shortage of opposition skeptics towards Prime Minister Lord North’s plan, but overwhelmingly, the Parliament ratified what became known as the Coercive Acts in England and the Intolerable Acts in America.

The collective punishment rested on four primary legs.

The port of Boston was closed and blockaded to all commercial traffic until full restitution for the lost tea was made to the satisfaction of the East India Company and the King.

The elected assembly was dissolved in favor of the authority of the Royal governor, who assumed control over all appointments and offices without the consent of the governed.

Trial by a jury of peers was suspended under a Royal writ that gave the governor authority to arrest, detain and try an accused defendant wherever he so chose.

Colonists were ordered to house British soldiers on their property at their own expense and against their will.

The full result was economic privation, building anger, defiance, resolve and cooperation. The man whose cartoon had urged colonial unity behind the King against the French was now being used as a symbol of a new cause.

British forces steadily built up in Boston until they marched out of the city which they controlled, and into the Patriot-controlled countryside on April 19, 1775, to arrest the leaders of the Tea Party, Samuel Adams and John Hancock and to seize the powder, cannon and weapons of the colonial militia.

Shortly after dawn, eight colonists were killed by British forces in Lexington.

British forces continued forward until they were met by 400 colonial militia at the Old Bridge in Concord. This is where the shot heard round the world was fired. This is where the American Revolution exploded. Before the day was at its end, hundreds of British troops were casualties as they retreated back into Boston in chaos.

The ensuing carnage at Breeds and Bunker Hill made perfectly clear that the war ahead was unstoppable, but the decision that was obvious was not yet clear.

This was the scene that greeted Franklin on his return to Philadelphia in May 1775. He was immediately asked to serve Pennsylvania as a delegate to the Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia that was far from organized – or even particularly coherent around what to do.

The debates raged for a year, and so did the paralysis, but by July 2, 1776, the Congress was ready to take a momentous vote. Interestingly, it is not the dysfunction, frustration, rivalries or intrigues that are well-tempered, but rather, the monumental achievement.

The Congress was ready to declare that the 13 colonies had become the United States of America, an independent nation, and to assert a list of grievances to the King written by Thomas Jefferson, and shaped by Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston, that would be titled “A Declaration of Independence.”

Within the declaration there was an assertion that obliterated all of what had come before, that was steeped in a transcendent hypocrisy as great as its perfection.

Words rang out from Philadelphia in July of 1776 and spread across the colonies. They were reprinted on the presses as they travelled to every nook and cranny of the then new country and across the ocean, and ultimately, to every corner of Earth as an aspiration and ideal that rings as true today as it was then.

All Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.

The world has never been the same.

A great civil war would be fought and won by the United States and the patriot cause. The cost would be enormous. Six hundred and twenty thousand would die, and thousands more families would be shattered like Franklin’s. His son stayed loyal to the King, and they never reconciled.

A tenuous peace would emerge from the war. A fractious coalition of disparate colonies laid out on the North American coast struggled to find its way towards a new government that could prove the proposition that ordinary people were capable of self-government and could restrain the savagery of man into a nation of laws.

The men who were tasked with the work include these names: George Washington, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and of course Benjamin Franklin, who was 85 years old in 1787, when their Constitution of the United States of America was unveiled.

Its preamble reads: “We the People …”

Today, it stands as the oldest and most durable constitution of a free people in human history. It is a work of transcendent genius and the foundation of our American civilization. Before he died, Franklin would see the first ten amendments to the US Constitution passed. They are known as the Bill of Rights, and they have endured through that day until this day. It is miraculous and the birthright of every human being who is so fortunate to be able to call themselves an American. It is our common bond.

The story of America is the story of man’s imperfections, failings and hypocrisies judged against the transcendent power of perfect ideals.

What right does this generation of Americans have to look back on such achievements with anger and disdain, while simultaneously lacking any energy, conviction and determination to perfect the American union in their time?

Judging the past takes only a lack of humility and a dash of arrogance.

Learning from it requires patience, understanding and humility. What the founding generation of Americans achieved was not a perfect society, but rather a vehicle that could perfect it over time with each generation building on what had come before. The limits of America’s possibilities and story have always been the limits of the human condition and spirit. There can be no other way in a system of organizing the affairs of a free people into a government of the people, by the people, for the people.

It is the duty of all Americans to know our story and all good citizens to have gratitude for what we have been bequeathed in a struggle of momentous dimensions where the “moral arc of the universe” has bended towards justice.

At the end of his life – nearing the end of the 18th century – Benjamin Franklin was called out by a woman as he was leaving Independence Hall and the constitutional convention.

“What have you given us, Dr. Franklin?” she said.

“A republic if you can keep it,” replied Benjamin Franklin.

There is no generation that has ever given a greater gift to another than this gift given to us by a defiant group of Englishmen. Let us honor their defiance in practice, but also with gratitude. They created the United States of America. America can save the world. It has already.

Thank you for an excellent, concise reminder of our history. As an aside, that Franklin was 85 years old in 1787, active in the creation and fulfillment of our Constitution in Philadelphia's hot, suffocating Independence Hall, should give pause to the many who claim that, Americans in their 80s today, are too old to govern.

“Franklin invented bifocals, and the lightning rod as part of ground-breaking experiments with electricity, paper money, the existence of the Gulf Stream, the first public libraries, insurance companies, volunteer fire departments and dozens of other public institutions that remain recognizable anchors of modern civil society.”

Excellent history lesson Steve. Little known fact: Franklin also invented the first unitary catheter for his brother James, who suffered from kidney stones.

Additionally, let’s not forget that the East India Tea Company monopoly, and the Tea Act was just the last straw. Other major factors of the war included; greater restrictions of the colonies, and more importantly, forcing rhetorical colonies to pay England for its defense during the French and Indian War.

Causes of the Revolutionary War: Taxation without representation. The Stamp Act, Townshend Act, and these Intolerable Acts taxed colonists without consent through Parliament.

Bottom line: the colonies were at a breaking point!…:)